Symfony and HTTP Fundamentals

Warning: You are browsing the documentation for Symfony 6.2, which is no longer maintained.

Read the updated version of this page for Symfony 8.0 (the current stable version).

Symfony and HTTP Fundamentals

Great news! While you're learning Symfony, you're also learning the fundamentals of the web. Symfony is closely modeled after the HTTP Request-Response flow: that fundamental paradigm that's behind almost all communication on the web.

In this article, you'll walk through the HTTP fundamentals and find out how these are applied throughout Symfony.

Requests and Responses in HTTP

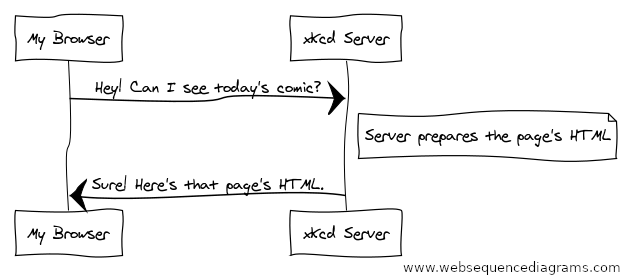

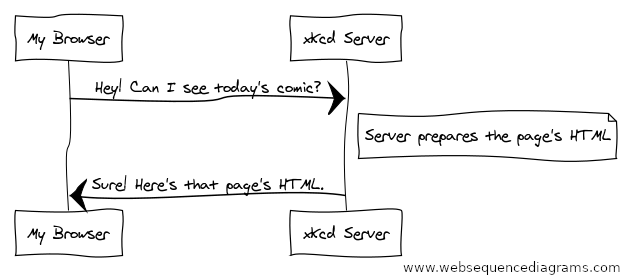

HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) is a text language that allows two machines to communicate with each other. For example, when checking for the latest xkcd comic, the following (approximate) conversation takes place:

HTTP is the term used to describe this text-based language. The goal of your server is always to understand text requests and return text responses.

Symfony is built from the ground up around that reality. Whether you realize it or not, HTTP is something you use every day. With Symfony, you'll learn how to master it.

Step 1: The Client Sends a Request

Every conversation on the web starts with a request. The request is a text message created by a client (e.g. a browser, a smartphone app, etc) in a special format known as HTTP. The client sends that request to a server, and then waits for the response.

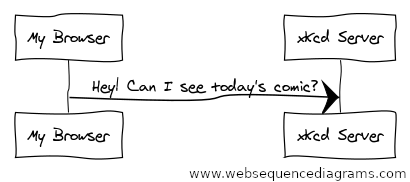

Take a look at the first part of the interaction (the request) between a browser and the xkcd web server:

In HTTP-speak, this HTTP request would actually look something like this:

1 2 3 4

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: xkcd.com

Accept: text/html

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh)These few lines communicate everything necessary about exactly which

resource the client is requesting. The first line of an HTTP request is the

most important, because it contains two important things: the HTTP method (GET)

and the URI (/).

The URI (e.g. /, /contact, etc) is the unique address or location

that identifies the resource the client wants. The HTTP method (e.g. GET)

defines what the client wants to do with the resource. The HTTP methods (also

known as verbs) define the few common ways that the client can act upon the

resource - the most common HTTP methods are:

- GET

- Retrieve the resource from the server (e.g. when visiting a page);

- POST

- Create a resource on the server (e.g. when submitting a form);

- PUT/PATCH

- Update the resource on the server (used by APIs);

- DELETE

- Delete the resource from the server (used by APIs).

With this in mind, you can imagine what an HTTP request might look like to delete a specific blog post, for example:

1

DELETE /blog/15 HTTP/1.1Note

There are actually nine HTTP methods defined by the HTTP specification,

but many of them are not widely used or supported. In reality, many

modern browsers only support POST and GET in HTML forms. Various

others are however supported in XMLHttpRequest.

In addition to the first line, an HTTP request invariably contains other

lines of information called request headers. The headers can supply a wide

range of information such as the host of the resource being requested (Host),

the response formats the client accepts (Accept) and the application the

client is using to make the request (User-Agent). Many other headers exist

and can be found on Wikipedia's List of HTTP header fields article.

Step 2: The Server Returns a Response

Once a server has received the request, it knows exactly which resource the client needs (via the URI) and what the client wants to do with that resource (via the method). For example, in the case of a GET request, the server prepares the resource and returns it in an HTTP response. Consider the response from the xkcd web server:

Translated into HTTP, the response sent back to the browser will look something like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Sat, 02 Apr 2011 21:05:05 GMT

Server: lighttpd/1.4.19

Content-Type: text/html

<html>

<!-- ... HTML for the xkcd comic -->

</html>The HTTP response contains the requested resource (the HTML content in this case), as well as other information about the response. The first line is especially important and contains the HTTP response status code (200 in this case).

The status code communicates the overall outcome of the request back to the client. Was the request successful? Was there an error? Different status codes exist that indicate success, an error or that the client needs to do something (e.g. redirect to another page). Check out the list of HTTP status codes.

Like the request, an HTTP response contains additional pieces of information

known as HTTP headers. The body of the same resource could be returned in multiple

different formats like HTML, XML or JSON and the Content-Type header uses

Internet Media Types like text/html to tell the client which format is

being returned. You can see a List of common media types from IANA.

Many other headers exist, some of which are very powerful. For example, certain headers can be used to create a powerful caching system.

Requests, Responses and Web Development

This request-response conversation is the fundamental process that drives all communication on the web.

The most important fact is this: regardless of the language you use, the type of application you build (web, mobile, JSON API) or the development philosophy you follow, the end goal of an application is always to understand each request and create and return the appropriate response.

See also

To learn more about the HTTP specification, read the original HTTP 1.1 RFC or the HTTP Bis, which is an active effort to clarify the original specification.

Requests and Responses in PHP

So how do you interact with the "request" and create a "response" when using PHP? In reality, PHP abstracts you a bit from the whole process:

1 2 3 4 5 6

$uri = $_SERVER['REQUEST_URI'];

$foo = $_GET['foo'];

header('Content-Type: text/html');

echo 'The URI requested is: '.$uri;

echo 'The value of the "foo" parameter is: '.$foo;As strange as it sounds, this small application is in fact taking information

from the HTTP request and using it to create an HTTP response. Instead of

parsing the raw HTTP request message, PHP prepares superglobal variables

(such as $_SERVER and $_GET) that contain all the information from the

request. Similarly, instead of returning the HTTP-formatted text response, you

can use the PHP header function to create response headers and

print out the actual content that will be the content portion of the response

message. PHP will create a true HTTP response and return it to the client:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Sat, 03 Apr 2011 02:14:33 GMT

Server: Apache/2.2.17 (Unix)

Content-Type: text/html

The URI requested is: /testing?foo=symfony

The value of the "foo" parameter is: symfonyRequests and Responses in Symfony

Symfony provides an alternative to the raw PHP approach via two classes that allow you to interact with the HTTP request and response in an easier way.

Symfony Request Object

The Request class is an object-oriented representation of the HTTP request message. With it, you have all the request information at your fingertips:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26

use Symfony\Component\HttpFoundation\Request;

$request = Request::createFromGlobals();

// the URI being requested (e.g. /about) minus any query parameters

$request->getPathInfo();

// retrieves $_GET and $_POST variables respectively

$request->query->get('id');

$request->request->get('category', 'default category');

// retrieves $_SERVER variables

$request->server->get('HTTP_HOST');

// retrieves an instance of UploadedFile identified by "attachment"

$request->files->get('attachment');

// retrieves a $_COOKIE value

$request->cookies->get('PHPSESSID');

// retrieves an HTTP request header, with normalized, lowercase keys

$request->headers->get('host');

$request->headers->get('content-type');

$request->getMethod(); // e.g. GET, POST, PUT, DELETE or HEAD

$request->getLanguages(); // an array of languages the client acceptsAs a bonus, the Request class does a lot of work in the background about which

you will never need to worry. For example, the isSecure() method

checks the three different values in PHP that can indicate whether or not

the user is connecting via a secure connection (i.e. HTTPS).

Symfony Response Object

Symfony also provides a Response class: a PHP representation of an HTTP response message. This allows your application to use an object-oriented interface to construct the response that needs to be returned to the client:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

use Symfony\Component\HttpFoundation\Response;

$response = new Response();

$response->setContent('<html><body><h1>Hello world!</h1></body></html>');

$response->setStatusCode(Response::HTTP_OK);

// sets a HTTP response header

$response->headers->set('Content-Type', 'text/html');

// prints the HTTP headers followed by the content

$response->send();There are also several response sub-classes to help you return JSON, redirect, stream file downloads and more.

Tip

The Request and Response classes are part of a standalone component

called symfony/http-foundation

that you can use in any PHP project. This also contains classes for handling

sessions, file uploads and more.

If Symfony offered nothing else, you would already have a toolkit for accessing request information and an object-oriented interface for creating the response. Even as you learn the many powerful features in Symfony, keep in mind that the goal of your application is always to interpret a request and create the appropriate response based on your application logic.

The Journey from the Request to the Response

Like HTTP itself, using the Request and Response objects is pretty

straightforward. The hard part of building an application is writing what comes in

between. In other words, the real work comes in writing the code that

interprets the request information and creates the response.

Your application probably does many things, like sending emails, handling form submissions, saving things to a database, rendering HTML pages and protecting content with security. How can you manage all of this and still keep your code organized and maintainable? Symfony was created to help you with these problems.

The Front Controller

Traditionally, applications were built so that each "page" of a site was

its own physical file (e.g. index.php, contact.php, etc.).

There are several problems with this approach, including the inflexibility

of the URLs (what if you wanted to change blog.php to news.php without

breaking all of your links?) and the fact that each file must manually

include some set of core files so that security, database connections and

the "look" of the site can remain consistent.

A much better solution is to use a front controller: a single PHP file that handles every request coming into your application. For example:

/index.php |

executes index.php |

/index.php/contact |

executes index.php |

/index.php/blog |

executes index.php |

Tip

By using rewrite rules in your

web server configuration,

the index.php won't be needed and you will have beautiful, clean URLs

(e.g. /show).

Now, every request is handled exactly the same way. Instead of individual URLs executing different PHP files, the front controller is always executed, and the routing of different URLs to different parts of your application is done internally.

A small front controller might look like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

// index.php

use Symfony\Component\HttpFoundation\Request;

use Symfony\Component\HttpFoundation\Response;

$request = Request::createFromGlobals();

$path = $request->getPathInfo(); // the URI path being requested

if (in_array($path, ['', '/'])) {

$response = new Response('Welcome to the homepage.');

} elseif ('/contact' === $path) {

$response = new Response('Contact us');

} else {

$response = new Response('Page not found.', Response::HTTP_NOT_FOUND);

}

$response->send();This is better, but this is still a lot of repeated work! Fortunately, Symfony can help once again.

The Symfony Application Flow

A Symfony framework application also uses a front-controller file. But inside, Symfony is responsible for handling each incoming request and figuring out what to do:

Incoming requests are interpreted by the Routing component and

passed to PHP functions that return Response objects.

This may not make sense yet, but as you keep reading, you'll learn about routes and controllers: the two fundamental parts to creating a page. But as you go along, don't forget that no matter how complex your app gets, your job is always the same: read information from the Request and use it to create a Response.

Summary: The Request-Response Flow

Here's what we've learned so far:

- A client (e.g. a browser) sends an HTTP request;

- Each request executes the same, single file (called a "front controller");

- The front controller boots Symfony and passes the request information;

- Internally, Symfony uses routes and controllers to create the Response for the page (we'll learn about these soon!);

- Symfony turns your

Responseobject into the text headers and content (i.e. the HTTP response), which are sent back to the client.