Security

Warning: You are browsing the documentation for Symfony 2.x, which is no longer maintained.

Read the updated version of this page for Symfony 8.0 (the current stable version).

Symfony's security system is incredibly powerful, but it can also be confusing to set up. In this article you'll learn how to set up your application's security step-by-step, from configuring your firewall and how you load users, to denying access and fetching the User object. Depending on what you need, sometimes the initial setup can be tough. But once it's done, Symfony's security system is both flexible and (hopefully) fun to work with.

Since there's a lot to talk about, this article is organized into a few big sections:

- Initial

security.ymlsetup (authentication); - Denying access to your app (authorization);

- Fetching the current User object.

These are followed by a number of small (but still captivating) sections, like logging out and encoding user passwords.

1) Initial security.yml Setup (Authentication)

The security system is configured in app/config/security.yml. The default

configuration looks like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

# app/config/security.yml

security:

providers:

in_memory:

memory: ~

firewalls:

dev:

pattern: ^/(_(profiler|wdt)|css|images|js)/

security: false

main:

anonymous: ~The firewalls key is the heart of your security configuration. The

dev firewall isn't important, it just makes sure that Symfony's development

tools - which live under URLs like /_profiler and /_wdt aren't blocked

by your security.

Tip

You can also match a request against other details of the request (e.g. host). For more information and examples read How to Restrict Firewalls to a Specific Request.

All other URLs will be handled by the main firewall (no pattern

key means it matches all URLs). You can think of the firewall like your

security system, and so it usually makes sense to have just one main firewall.

But this does not mean that every URL requires authentication - the anonymous

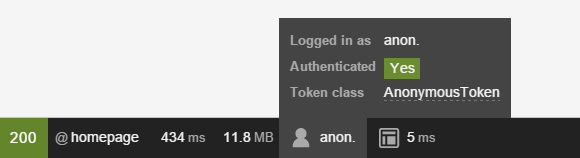

key takes care of this. In fact, if you go to the homepage right now, you'll

have access and you'll see that you're "authenticated" as anon.. Don't

be fooled by the "Yes" next to Authenticated, you're just an anonymous user:

You'll learn later how to deny access to certain URLs or controllers.

Tip

Security is highly configurable and there's a Security Configuration Reference that shows all of the options with some extra explanation.

A) Configuring how your Users will Authenticate

The main job of a firewall is to configure how your users will authenticate. Will they use a login form? HTTP basic authentication? An API token? All of the above?

Let's start with HTTP basic authentication (the old-school prompt) and work up from there.

To activate this, add the http_basic key under your firewall:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

# app/config/security.yml

security:

# ...

firewalls:

# ...

main:

anonymous: ~

http_basic: ~Simple! To try this, you need to require the user to be logged in to see

a page. To make things interesting, create a new page at /admin. For

example, if you use annotations, create something like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

// src/AppBundle/Controller/DefaultController.php

// ...

use Sensio\Bundle\FrameworkExtraBundle\Configuration\Route;

use Symfony\Bundle\FrameworkBundle\Controller\Controller;

use Symfony\Component\HttpFoundation\Response;

class DefaultController extends Controller

{

/**

* @Route("/admin")

*/

public function adminAction()

{

return new Response('<html><body>Admin page!</body></html>');

}

}Next, add an access_control entry to security.yml that requires the

user to be logged in to access this URL:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

# app/config/security.yml

security:

# ...

firewalls:

# ...

main:

# ...

access_control:

# require ROLE_ADMIN for /admin*

- { path: ^/admin, roles: ROLE_ADMIN }Note

You'll learn more about this ROLE_ADMIN thing and denying access

later in the Security section.

Great! Now, if you go to /admin, you'll see the HTTP basic auth prompt:

But who can you login as? Where do users come from?

Tip

Want to use a traditional login form? Great! See How to Build a Traditional Login Form. What other methods are supported? See the Configuration Reference or build your own.

Tip

If your application logs users in via a third-party service such as Google, Facebook or Twitter, check out the HWIOAuthBundle community bundle.

B) Configuring how Users are Loaded

When you type in your username, Symfony needs to load that user's information from somewhere. This is called a "user provider", and you're in charge of configuring it. Symfony has a built-in way to load users from the database, or you can create your own user provider.

The easiest (but most limited) way, is to configure Symfony to load hardcoded

users directly from the security.yml file itself. This is called an "in memory"

provider, but it's better to think of it as an "in configuration" provider:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

# app/config/security.yml

security:

providers:

in_memory:

memory:

users:

ryan:

password: ryanpass

roles: 'ROLE_USER'

admin:

password: kitten

roles: 'ROLE_ADMIN'

# ...Like with firewalls, you can have multiple providers, but you'll

probably only need one. If you do have multiple, you can configure which

one provider to use for your firewall under its provider key (e.g.

provider: in_memory).

See also

See How to Use multiple User Providers for all the details about multiple providers setup.

Try to login using username admin and password kitten. You should

see an error!

No encoder has been configured for account "Symfony\Component\Security\Core\User\User"

To fix this, add an encoders key:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

# app/config/security.yml

security:

# ...

encoders:

Symfony\Component\Security\Core\User\User: plaintext

# ...User providers load user information and put it into a User object. If

you load users from the database

or some other source, you'll

use your own custom User class. But when you use the "in memory" provider,

it gives you a Symfony object.

Whatever your User class is, you need to tell Symfony what algorithm was

used to encode the passwords. In this case, the passwords are just plaintext,

but in a second, you'll change this to use bcrypt.

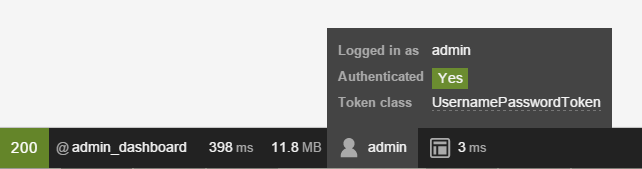

If you refresh now, you'll be logged in! The web debug toolbar even tells you who you are and what roles you have:

Because this URL requires ROLE_ADMIN, if you had logged in as ryan,

this would deny you access. More on that later (Security).

Loading Users from the Database

If you'd like to load your users via the Doctrine ORM, that's easy! See How to Load Security Users from the Database (the Entity Provider) for all the details.

C) Encoding the User's Password

Whether your users are stored in security.yml, in a database or somewhere

else, you'll want to encode their passwords. The best algorithm to use is

bcrypt:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

# app/config/security.yml

security:

# ...

encoders:

Symfony\Component\Security\Core\User\User:

algorithm: bcrypt

cost: 12Caution

If you're using PHP 5.4 or lower, you'll need to install the ircmaxell/password-compat

library via Composer in order to be able to use the bcrypt encoder:

1

$ composer require ircmaxell/password-compat "~1.0"Of course, your users' passwords now need to be encoded with this exact algorithm. For hardcoded users, since 2.7 you can use the built-in command:

1

$ php app/console security:encode-passwordIt will give you something like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

# app/config/security.yml

security:

# ...

providers:

in_memory:

memory:

users:

ryan:

password: $2a$12$LCY0MefVIEc3TYPHV9SNnuzOfyr2p/AXIGoQJEDs4am4JwhNz/jli

roles: 'ROLE_USER'

admin:

password: $2a$12$cyTWeE9kpq1PjqKFiWUZFuCRPwVyAZwm4XzMZ1qPUFl7/flCM3V0G

roles: 'ROLE_ADMIN'Everything will now work exactly like before. But if you have dynamic users (e.g. from a database), how can you programmatically encode the password before inserting them into the database? Don't worry, see How to Manually Encode a Password for details.

Tip

Supported algorithms for this method depend on your PHP version, but

include the algorithms returned by the PHP function hash_algos

as well as a few others (e.g. bcrypt). See the encoders key in the

Security Reference Section

for examples.

It's also possible to use different hashing algorithms on a user-by-user basis. See How to Choose the Password Encoder Algorithm Dynamically for more details.

D) Configuration Done!

Congratulations! You now have a working authentication system that uses HTTP

basic auth and loads users right from the security.yml file.

Your next steps depend on your setup:

- Configure a different way for your users to login, like a login form or something completely custom;

- Load users from a different source, like the database or some other source;

- Learn how to deny access, load the User object and deal with roles in the Authorization section.

2) Denying Access, Roles and other Authorization

Users can now login to your app using http_basic or some other method.

Great! Now, you need to learn how to deny access and work with the User object.

This is called authorization, and its job is to decide if a user can

access some resource (a URL, a model object, a method call, ...).

The process of authorization has two different sides:

- The user receives a specific set of roles when logging in (e.g.

ROLE_ADMIN). - You add code so that a resource (e.g. URL, controller) requires a specific

"attribute" (most commonly a role like

ROLE_ADMIN) in order to be accessed.

Tip

In addition to roles (e.g. ROLE_ADMIN), you can protect a resource

using other attributes/strings (e.g. EDIT) and use voters or Symfony's

ACL system to give these meaning. This might come in handy if you need

to check if user A can "EDIT" some object B (e.g. a Product with id 5).

See Security.

Roles

When a user logs in, they receive a set of roles (e.g. ROLE_ADMIN). In

the example above, these are hardcoded into security.yml. If you're

loading users from the database, these are probably stored on a column

in your table.

Caution

All roles you assign to a user must begin with the ROLE_ prefix.

Otherwise, they won't be handled by Symfony's security system in the

normal way (i.e. unless you're doing something advanced, assigning a

role like FOO to a user and then checking for FOO as described

below will not work).

Roles are simple, and are basically strings that you invent and use as needed.

For example, if you need to start limiting access to the blog admin section

of your website, you could protect that section using a ROLE_BLOG_ADMIN

role. This role doesn't need to be defined anywhere - you can just start using

it.

Tip

Make sure every user has at least one role, or your user will look

like they're not authenticated. A common convention is to give every

user ROLE_USER.

You can also specify a role hierarchy where some roles automatically mean that you also have other roles.

Add Code to Deny Access

There are two ways to deny access to something:

- access_control in security.yml

allows you to protect URL patterns (e.g.

/admin/*). This is easy, but less flexible; - in your code via the security.authorization_checker service.

Securing URL patterns (access_control)

The most basic way to secure part of your application is to secure an entire

URL pattern. You saw this earlier, where anything matching the regular expression

^/admin requires the ROLE_ADMIN role:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

# app/config/security.yml

security:

# ...

firewalls:

# ...

main:

# ...

access_control:

# require ROLE_ADMIN for /admin*

- { path: ^/admin, roles: ROLE_ADMIN }This is great for securing entire sections, but you'll also probably want to secure your individual controllers as well.

You can define as many URL patterns as you need - each is a regular expression.

BUT, only one will be matched. Symfony will look at each starting

at the top, and stop as soon as it finds one access_control entry that

matches the URL.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

# app/config/security.yml

security:

# ...

access_control:

- { path: ^/admin/users, roles: ROLE_SUPER_ADMIN }

- { path: ^/admin, roles: ROLE_ADMIN }Prepending the path with ^ means that only URLs beginning with the

pattern are matched. For example, a path of simply /admin (without

the ^) would match /admin/foo but would also match URLs like /foo/admin.

Securing Controllers and other Code

You can easily deny access from inside a controller:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

// ...

public function helloAction($name)

{

// The second parameter is used to specify on what object the role is tested.

$this->denyAccessUnlessGranted('ROLE_ADMIN', null, 'Unable to access this page!');

// Old way :

// if (false === $this->get('security.authorization_checker')->isGranted('ROLE_ADMIN')) {

// throw $this->createAccessDeniedException('Unable to access this page!');

// }

// ...

}In both cases, a special AccessDeniedException is thrown, which ultimately triggers a 403 HTTP response inside Symfony.

That's it! If the user isn't logged in yet, they will be asked to login (e.g.

redirected to the login page). If they are logged in, but do not have the

ROLE_ADMIN role, they'll be shown the 403 access denied page (which you can

customize). If they are logged in

and have the correct roles, the code will be executed.

Thanks to the SensioFrameworkExtraBundle, you can also secure your controller using annotations:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

// ...

use Sensio\Bundle\FrameworkExtraBundle\Configuration\Security;

/**

* @Security("has_role('ROLE_ADMIN')")

*/

public function helloAction($name)

{

// ...

}For more information, see the FrameworkExtraBundle documentation.

Access Control in Templates

If you want to check if the current user has a role inside a template, use

the built-in is_granted() helper function:

1 2 3

{% if is_granted('ROLE_ADMIN') %}

<a href="...">Delete</a>

{% endif %}Note

In Symfony versions previous to 2.8, using the is_granted() function

in a page that wasn't behind a firewall resulted in an exception. That's why

you also needed to check first for the existence of the user:

1

{% if app.user and is_granted('ROLE_ADMIN') %}Starting from Symfony 2.8, the app.user and ... check is no longer needed.

Securing other Services

Anything in Symfony can be protected by doing something similar to the code used to secure a controller. For example, suppose you have a service (i.e. a PHP class) whose job is to send emails. You can restrict use of this class - no matter where it's being used from - to only certain users.

For more information see How to Secure any Service or Method in your Application.

Checking to see if a User is Logged In (IS_AUTHENTICATED_FULLY)

So far, you've checked access based on roles - those strings that start with

ROLE_ and are assigned to users. But if you only want to check if a

user is logged in (you don't care about roles), then you can use

IS_AUTHENTICATED_FULLY:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

// ...

public function helloAction($name)

{

if (!$this->get('security.authorization_checker')->isGranted('IS_AUTHENTICATED_FULLY')) {

throw $this->createAccessDeniedException();

}

// ...

}Tip

You can of course also use this in access_control.

IS_AUTHENTICATED_FULLY isn't a role, but it kind of acts like one, and every

user that has successfully logged in will have this. In fact, there are three

special attributes like this:

IS_AUTHENTICATED_REMEMBERED: All logged in users have this, even if they are logged in because of a "remember me cookie". Even if you don't use the remember me functionality, you can use this to check if the user is logged in.IS_AUTHENTICATED_FULLY: This is similar toIS_AUTHENTICATED_REMEMBERED, but stronger. Users who are logged in only because of a "remember me cookie" will haveIS_AUTHENTICATED_REMEMBEREDbut will not haveIS_AUTHENTICATED_FULLY.IS_AUTHENTICATED_ANONYMOUSLY: All users (even anonymous ones) have this - this is useful when whitelisting URLs to guarantee access - some details are in How Does the Security access_control Work?.

You can also use expressions inside your templates:

1 2 3 4 5

{% if is_granted(expression(

'"ROLE_ADMIN" in roles or (not is_anonymous() and user.isSuperAdmin())'

)) %}

<a href="...">Delete</a>

{% endif %}For more details on expressions and security, see Security: Complex Access Controls with Expressions.

Access Control Lists (ACLs): Securing individual Database Objects

Imagine you are designing a blog where users can comment on your posts. You also want a user to be able to edit their own comments, but not those of other users. Also, as the admin user, you yourself want to be able to edit all comments.

To accomplish this you have 2 options:

- Voters allow you to write own business logic (e.g. the user can edit this post because they were the creator) to determine access. You'll probably want this option - it's flexible enough to solve the above situation.

- ACLs allow you to create a database structure where you can assign any arbitrary user any access (e.g. EDIT, VIEW) to any object in your system. Use this if you need an admin user to be able to grant customized access across your system via some admin interface.

In both cases, you'll still deny access using methods similar to what was shown above.

3) Retrieving the User Object

After authentication, the User object of the current user can be accessed

via the security.token_storage service. From inside a controller, this will

look like:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

public function indexAction()

{

if (!$this->get('security.authorization_checker')->isGranted('IS_AUTHENTICATED_FULLY')) {

throw $this->createAccessDeniedException();

}

$user = $this->getUser();

// the above is a shortcut for this

$user = $this->get('security.token_storage')->getToken()->getUser();

}Tip

The user will be an object and the class of that object will depend on your user provider.

Now you can call whatever methods are on your User object. For example,

if your User object has a getFirstName() method, you could use that:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

use Symfony\Component\HttpFoundation\Response;

// ...

public function indexAction()

{

// ...

return new Response('Well hi there '.$user->getFirstName());

}Always Check if the User is Logged In

It's important to check if the user is authenticated first. If they're not,

$user will either be null or the string anon.. Wait, what? Yes,

this is a quirk. If you're not logged in, the user is technically the string

anon., though the getUser() controller shortcut converts this to

null for convenience.

The point is this: always check to see if the user is logged in before using

the User object, and use the isGranted() method (or

access_control) to do this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

// yay! Use this to see if the user is logged in

if (!$this->get('security.authorization_checker')->isGranted('IS_AUTHENTICATED_FULLY')) {

throw $this->createAccessDeniedException();

}

// boo :(. Never check for the User object to see if they're logged in

if ($this->getUser()) {

}Retrieving the User in a Template

In a Twig Template this object can be accessed via the app.user key:

1 2 3

{% if is_granted('IS_AUTHENTICATED_FULLY') %}

<p>Username: {{ app.user.username }}</p>

{% endif %}Logging Out

Caution

Notice that when using http-basic authenticated firewalls, there is no real way to log out : the only way to log out is to have the browser stop sending your name and password on every request. Clearing your browser cache or restarting your browser usually helps. Some web developer tools might be helpful here too.

Usually, you'll also want your users to be able to log out. Fortunately,

the firewall can handle this automatically for you when you activate the

logout config parameter:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

# app/config/security.yml

security:

# ...

firewalls:

secured_area:

# ...

logout:

path: /logout

target: /Next, you'll need to create a route for this URL (but not a controller):

1 2 3

# app/config/routing.yml

logout:

path: /logoutAnd that's it! By sending a user to /logout (or whatever you configure

the path to be), Symfony will un-authenticate the current user.

Once the user has been logged out, they will be redirected to whatever path

is defined by the target parameter above (e.g. the homepage).

Tip

If you need to do something more interesting after logging out, you can

specify a logout success handler by adding a success_handler key

and pointing it to a service id of a class that implements

LogoutSuccessHandlerInterface.

See Security Configuration Reference.

Hierarchical Roles

Instead of associating many roles to users, you can define role inheritance rules by creating a role hierarchy:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

# app/config/security.yml

security:

# ...

role_hierarchy:

ROLE_ADMIN: ROLE_USER

ROLE_SUPER_ADMIN: [ROLE_ADMIN, ROLE_ALLOWED_TO_SWITCH]In the above configuration, users with ROLE_ADMIN role will also have the

ROLE_USER role. The ROLE_SUPER_ADMIN role has ROLE_ADMIN, ROLE_ALLOWED_TO_SWITCH

and ROLE_USER (inherited from ROLE_ADMIN).

Note

The value of the role_hierarchy option is defined statically, so you

can't for example store the role hierarchy in a database. If you need that,

create a custom security voter that looks for the

user roles in the database.

Final Words

Woh! Nice work! You now know more than the basics of security. The hardest parts are when you have custom requirements: like a custom authentication strategy (e.g. API tokens), complex authorization logic and many other things (because security is complex!).

Fortunately, there are a lot of articles aimed at describing many of these situations. Also, see the Security Reference Section. Many of the options don't have specific details, but seeing the full possible configuration tree may be useful.

Good luck!

Learn More

Authentication (Identifying/Logging in the User)

- How to Build a Traditional Login Form

- Authenticating against an LDAP server

- How to Load Security Users from the Database (the Entity Provider)

- How to Create a Custom Authentication System with Guard

- How to Add "Remember Me" Login Functionality

- How to Impersonate a User

- How to Customize Redirect After Form Login

- How to Create a custom User Provider

- How to Create a Custom Form Password Authenticator

- How to Authenticate Users with API Keys

- How to Create a custom Authentication Provider

- Using pre Authenticated Security Firewalls

- Using CSRF Protection in the Login Form

- How to Choose the Password Encoder Algorithm Dynamically

- How to Use multiple User Providers

- How to Use Multiple Guard Authenticators

- How to Restrict Firewalls to a Specific Request

- How to Restrict Firewalls to a Specific Host

- How to Create and Enable Custom User Checkers