Much of the discussion so far has been devoted to building pages, and processing requests and responses. But the business logic of a web application relies mostly on its data model. Symfony's default model component is based on an object/relational mapping layer. Symfony comes bundles with the two most popular PHP ORMs: Propel and Doctrine. In a symfony application, you access data stored in a database and modify it through objects; you never address the database explicitly. This maintains a high level of abstraction and portability.

This chapter explains how to create an object data model, and the way to access and modify the data in Doctrine. It also demonstrates the integration of Doctrine in Symfony.

tip

If you want to use Propel instead of Doctrine, read Appendix A instead as it contains the exact same information but for Propel.

Why Use an ORM and an Abstraction Layer?

Databases are relational. PHP 5 and symfony are object-oriented. In order to most effectively access the database in an object-oriented context, an interface translating the object logic to the relational logic is required. As explained in Chapter 1, this interface is called an object-relational mapping (ORM), and it is made up of objects that give access to data and keep business rules within themselves.

The main benefit of an ORM is reusability, allowing the methods of a data object to be called from various parts of the application, even from different applications. The ORM layer also encapsulates the data logic--for instance, the calculation of a forum user rating based on how many contributions were made and how popular these contributions are. When a page needs to display such a user rating, it simply calls a method of the data model, without worrying about the details of the calculation. If the calculation changes afterwards, you will just need to modify the rating method in the model, leaving the rest of the application unchanged.

Using objects instead of records, and classes instead of tables, has another benefit: They allow you to add new accessors to your objects that don't necessarily match a column in a table. For instance, if you have a table called client with two fields named first_name and last_name, you might like to be able to require just a Name. In an object-oriented world, it is as easy as adding a new accessor method to the Client class, as in Listing 8-1. From the application point of view, there is no difference between the FirstName, LastName, and Name attributes of the Client class. Only the class itself can determine which attributes correspond to a database column.

Listing 8-1 - Accessors Mask the Actual Table Structure in a Model Class

public function getName() { return $this->getFirstName().' '.$this->getLastName(); }

All the repeated data-access functions and the business logic of the data itself can be kept in such objects. Suppose you have a ShoppingCart class in which you keep Items (which are objects). To get the full amount of the shopping cart for the checkout, write a custom method to encapsulate the actual calculation, as shown in Listing 8-2.

Listing 8-2 - Accessors Mask the Data Logic

public function getTotal() { $total = 0; foreach ($this->getItems() as $item) { $total += $item->getPrice() * $item->getQuantity(); } return $total; }

There is another important point to consider when building data-access procedures: Database vendors use different SQL syntax variants. Switching to another database management system (DBMS) forces you to rewrite part of the SQL queries that were designed for the previous one. If you build your queries using a database-independent syntax, and leave the actual SQL translation to a third-party component, you can switch database systems without pain. This is the goal of the database abstraction layer. It forces you to use a specific syntax for queries, and does the dirty job of conforming to the DBMS particulars and optimizing the SQL code.

The main benefit of an abstraction layer is portability, because it makes switching to another database possible, even in the middle of a project. Suppose that you need to write a quick prototype for an application, but the client hasn't decided yet which database system would best suit his needs. You can start building your application with SQLite, for instance, and switch to MySQL, PostgreSQL, or Oracle when the client is ready to decide. Just change one line in a configuration file, and it works.

Symfony uses Propel or Doctrine as the ORM, and they use PHP Data Objects for database abstraction. These two third-party components, both developed by the Propel and Doctrine teams, are seamlessly integrated into symfony, and you can consider them as part of the framework. Their syntax and conventions, described in this chapter, were adapted so that they differ from the symfony ones as little as possible.

note

In a symfony project, all the applications share the same model. That's the whole point of the project level: regrouping applications that rely on common business rules. This is the reason that the model is independent from the applications and the model files are stored in a lib/model/ directory at the root of the project.

Symfony's Database Schema

In order to create the data object model that symfony will use, you need to translate whatever relational model your database has to an object data model. The ORM needs a description of the relational model to do the mapping, and this is called a schema. In a schema, you define the tables, their relations, and the characteristics of their columns.

Symfony's syntax for schemas uses the YAML format. The schema.yml files must be located in the myproject/config/doctrine directory.

Schema Example

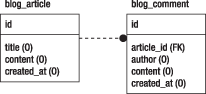

How do you translate a database structure into a schema? An example is the best way to understand it. Imagine that you have a blog database with two tables: blog_article and blog_comment, with the structure shown in Figure 8-1.

Figure 8-1 - A blog database table structure

The related schema.yml file should look like Listing 8-3.

Listing 8-3 - Sample schema.yml

Article:

actAs: [Timestampable]

tableName: blog_article

columns:

id:

type: integer

primary: true

autoincrement: true

title: string(255)

content: clob

Comment:

actAs: [Timestampable]

tableName: blog_comment

columns:

id:

type: integer

primary: true

autoincrement: true

article_id: integer

author: string(255)

content: clob

relations:

Article:

onDelete: CASCADE

foreignAlias: Comments

Notice that the name of the database itself (blog) doesn't appear in the schema.yml file. Instead, the database is described under a connection name (doctrine in this example). This is because the actual connection settings can depend on the environment in which your application runs. For instance, when you run your application in the development environment, you will access a development database (maybe blog_dev), but with the same schema as the production database. The connection settings will be specified in the databases.yml file, described in the "Database Connections" section later in this chapter. The schema doesn't contain any detailed connection to settings, only a connection name, to maintain database abstraction.

Basic Schema Syntax

In a schema.yml file, the first key represents a model name. You can specify multiple models, each having a set of columns. According to the YAML syntax, the keys end with a colon, and the structure is shown through indentation (one or more spaces, but no tabulations).

A model can have special attributes, including the tableName (the name of the models database table). If you don't mention a tableName for a model, Doctrine creates it based on the underscored version of the model name.

tip

The underscore convention adds underscores between words, and lowercases everything. The default underscored versions of Article and Comment are article and comment.

A model contains columns. The column value can be defined in two different ways:

If you define only one attribute, it is the column type. Symfony understands the usual column types:

boolean,integer,float,date,string(size),clob(converted, for instance, totextin MySQL), and so on.If you need to define other column attributes (like default value, required, and so on), you should write the column attributes as a set of

key: value. This extended schema syntax is described later in the chapter.

Models can also contain explicit foreign keys and indexes. Refer to the "Extended Schema Syntax" section later in this chapter to learn more.

Model Classes

The schema is used to build the model classes of the ORM layer. To save execution time, these classes are generated with a command-line task called doctrine:build-model.

$ php symfony doctrine:build-model

tip

After building your model, you must remember to clear symfony's internal cache with php symfony cc so symfony can find your newly created models.

Typing this command will launch the analysis of the schema and the generation of base data model classes in the lib/model/doctrine/base directory of your project:

BaseArticle.phpBaseComment.php

In addition, the actual data model classes will be created in lib/model/doctrine:

Article.phpArticleTable.phpComment.phpCommentTable.php

You defined only two models, and you end up with six files. There is nothing wrong, but it deserves some explanation.

Base and Custom Classes

Why keep two versions of the data object model in two different directories?

You will probably need to add custom methods and properties to the model objects (think about the getName() method in Listing 8-1). But as your project develops, you will also add tables or columns. Whenever you change the schema.yml file, you need to regenerate the object model classes by making a new call to doctrine:build-model. If your custom methods were written in the classes actually generated, they would be erased after each generation.

The Base classes kept in the lib/model/doctrine/base/ directory are the ones directly generated from the schema. You should never modify them, since every new build of the model will completely erase these files.

On the other hand, the custom object classes, kept in the lib/model/doctrine directory, actually inherit from the Base ones. When the doctrine:build-model task is called on an existing model, these classes are not modified. So this is where you can add custom methods.

Listing 8-4 presents an example of a custom model class as created by the first call to the doctrine:build-model task.

Listing 8-4 - Sample Model Class File, in lib/model/doctrine/Article.php

class Article extends BaseArticle { }

It inherits everything of the BaseArticle class, but a modification in the schema will not affect it.

The mechanism of custom classes extending base classes allows you to start coding, even without knowing the final relational model of your database. The related file structure makes the model both customizable and evolutionary.

Object and Table Classes

Article and Comment are object classes that represent a record in the database. They give access to the columns of a record and to related records. This means that you will be able to know the title of an article by calling a method of an Article object, as in the example shown in Listing 8-5.

Listing 8-5 - Getters for Record Columns Are Available in the Object Class

$article = new Article(); // ... $title = $article->getTitle();

ArticleTable and CommentTable are table classes; that is, classes that contain public methods to operate on the tables. They provide a way to retrieve records from the tables. Their methods usually return an object or a collection of objects of the related object class, as shown in Listing 8-6.

Listing 8-6 - Public Methods to Retrieve Records Are Available in the Table Class

// $article is an instance of class Article $article = Doctrine_Core::getTable('Article')->find(123);

Accessing Data

In symfony, your data is accessed through objects. If you are used to the relational model and using SQL to retrieve and alter your data, the object model methods will likely look complicated. But once you've tasted the power of object orientation for data access, you will probably like it a lot.

But first, let's make sure we share the same vocabulary. Relational and object data model use similar concepts, but they each have their own nomenclature:

| Relational | Object-Oriented |

|---|---|

| Table | Class |

| Row, record | Object |

| Field, column | Property |

Retrieving the Column Value

When symfony builds the model, it creates one base object class for each of the models defined in the schema.yml. Each of these classes comes with default accessors and mutators based on the column definitions: The new, getXXX(), and setXXX() methods help to create objects and give access to the object properties, as shown in Listing 8-7.

Listing 8-7 - Generated Object Class Methods

$article = new Article(); $article->setTitle('My first article'); $article->setContent("This is my very first article.\n Hope you enjoy it!"); $title = $article->getTitle(); $content = $article->getContent();

note

The generated object class is called Article but is stored in a table named blog_article in the database. If the tableName were not defined in the schema, the class would have been called article. The accessors and mutators use a camelCase variant of the column names, so the getTitle() method retrieves the value of the title column.

To set several fields at one time, you can use the fromArray() method, also available for each object class, as shown in Listing 8-8.

Listing 8-8 - The fromArray() Method Is a Multiple Setter

$article->fromArray(array( 'Title' => 'My first article', 'Content' => 'This is my very first article.\n Hope you enjoy it!', ));

Retrieving Related Records

The article_id column in the blog_comment table implicitly defines a foreign key to the blog_article table. Each comment is related to one article, and one article can have many comments. The generated classes contain five methods translating this relationship in an object-oriented way, as follows:

$comment->getArticle(): To get the relatedArticleobject$comment->getArticleId(): To get the ID of the relatedArticleobject$comment->setArticle($article): To define the relatedArticleobject$comment->setArticleId($id): To define the relatedArticleobject from an ID$article->getComments(): To get the relatedCommentobjects

The getArticleId() and setArticleId() methods show that you can consider the article_id column as a regular column and set the relationships by hand, but they are not very interesting. The benefit of the object-oriented approach is much more apparent in the three other methods. Listing 8-9 shows how to use the generated setters.

Listing 8-9 - Foreign Keys Are Translated into a Special Setter

$comment = new Comment(); $comment->setAuthor('Steve'); $comment->setContent('Gee, dude, you rock: best article ever!'); // Attach this comment to the previous $article object $comment->setArticle($article); // Alternative syntax // Only makes sense if the object is already saved in the database $comment->setArticleId($article->getId());

Listing 8-10 shows how to use the generated getters. It also demonstrates how to chain method calls on model objects.

Listing 8-10 - Foreign Keys Are Translated into Special Getters

// Many to one relationship echo $comment->getArticle()->getTitle(); => My first article echo $comment->getArticle()->getContent(); => This is my very first article. Hope you enjoy it! // One to many relationship $comments = $article->getComments();

The getArticle() method returns an object of class Article, which benefits from the getTitle() accessor. This is much better than doing the join yourself, which may take a few lines of code (starting from the $comment->getArticleId() call).

The $comments variable in Listing 8-10 contains an array of objects of class Comment. You can display the first one with $comments[0] or iterate through the collection with foreach ($comments as $comment).

Saving and Deleting Data

By calling the new constructor, you created a new object, but not an actual record in the blog_article table. Modifying the object has no effect on the database either. In order to save the data into the database, you need to call the save() method of the object.

$article->save();

The ORM is smart enough to detect relationships between objects, so saving the $article object also saves the related $comment object. It also knows if the saved object has an existing counterpart in the database, so the call to save() is sometimes translated in SQL by an INSERT, and sometimes by an UPDATE. The primary key is automatically set by the save() method, so after saving, you can retrieve the new primary key with $article->getId().

tip

You can check if an object is new by calling isNew(). And if you wonder if an object has been modified and deserves saving, call its isModified() method.

If you read comments to your articles, you might change your mind about the interest of publishing on the Internet. And if you don't appreciate the irony of article reviewers, you can easily delete the comments with the delete() method, as shown in Listing 8-11.

Listing 8-11 - Delete Records from the Database with the delete() Method on the Related Object

foreach ($article->getComments() as $comment) { $comment->delete(); }

Retrieving Records by Primary Key

If you know the primary key of a particular record, use the find() class method of the table class to get the related object.

$article = Doctrine_Core::getTable('Article')->find(7);

The schema.yml file defines the id field as the primary key of the blog_article table, so this statement will actually return the article that has id 7. As you used the primary key, you know that only one record will be returned; the $article variable contains an object of class Article.

In some cases, a primary key may consist of more than one column. In those cases, the find() method accepts multiple parameters, one for each primary key column.

Retrieving Records with Doctrine_Query

When you want to retrieve more than one record, you need to call the createQuery() method of the table class corresponding to the objects you want to retrieve. For instance, to retrieve objects of class Article, call Doctrine_Core::getTable('Article')->createQuery()->execute().

The first parameter of the execute() method is an array of parameters, which is the array of values to replace any placeholders found in your query.

An empty Doctrine_Query returns all the objects of the class. For instance, the code shown in Listing 8-12 retrieves all the articles.

Listing 8-12 - Retrieving Records by Doctrine_Query with createQuery()--Empty Query

$q = Doctrine_Core::getTable('Article')->createQuery(); $articles = $q->execute(); // Will result in the following SQL query SELECT b.id AS b__id, b.title AS b__title, b.content AS b__content, b.created_at AS b__created_at, b.updated_at AS b__updated_at FROM blog_article b

For a more complex object selection, you need an equivalent of the WHERE, ORDER BY, GROUP BY, and other SQL statements. The Doctrine_Query object has methods and parameters for all these conditions. For example, to get all comments written by Steve, ordered by date, build a Doctrine_Query as shown in Listing 8-13.

Listing 8-13 - Retrieving Records by a Doctrine_Query with createQuery()--Doctrine_Query with Conditions

$q = Doctrine_Core::getTable('Comment') ->createQuery('c') ->where('c.author = ?', 'Steve') ->orderBy('c.created_at ASC'); $comments = $q->execute(); // Will result in the following SQL query SELECT b.id AS b__id, b.article_id AS b__article_id, b.author AS b__author, b.content AS b__content, b.created_at AS b__created_at, b.updated_at AS b__updated_at FROM blog_comment b WHERE (b.author = ?) ORDER BY b.created_at ASC

Table 8-1 compares the SQL syntax with the Doctrine_Query object syntax.

Table 8-1 - SQL and Criteria Object Syntax

| SQL | Criteria |

|---|---|

WHERE column = value |

->where('acolumn = ?', 'value') |

| Other SQL Keywords | |

ORDER BY column ASC |

->orderBy('acolumn ASC') |

ORDER BY column DESC |

->addOrderBy('acolumn DESC') |

LIMIT limit |

->limit(limit) |

OFFSET offset |

->offset(offset) |

FROM table1 LEFT JOIN table2 ON table1.col1 = table2.col2 |

->leftJoin('a.Model2 m') |

FROM table1 INNER JOIN table2 ON table1.col1 = table2.col2 |

->innerJoin('a.Model2 m') |

Listing 8-14 shows another example of Doctrine_Query with multiple conditions. It retrieves all the comments by Steve on articles containing the word "enjoy," ordered by date.

Listing 8-14 - Another Example of Retrieving Records by Doctrine_Query with createQuery()--Doctrine_Query with Conditions

$q = Doctrine_Core::getTable('Comment') ->createQuery('c') ->where('c.author = ?', 'Steve') ->leftJoin('c.Article a') ->andWhere('a.content LIKE ?', '%enjoy%') ->orderBy('c.created_at ASC'); $comments = $q->execute(); // Will result in the following SQL query SELECT b.id AS b__id, b.article_id AS b__article_id, b.author AS b__author, b.content AS b__content, b.created_at AS b__created_at, b.updated_at AS b__updated_at, b2.id AS b2__id, b2.title AS b2__title, b2.content AS b2__content, b2.created_at AS b2__created_at, b2.updated_at AS b2__updated_at FROM blog_comment b LEFT JOIN blog_article b2 ON b.article_id = b2.id WHERE (b.author = ? AND b2.content LIKE ?) ORDER BY b.created_at ASC

Just as SQL is a simple language that allows you to build very complex queries, the Doctrine_Query object can handle conditions with any level of complexity. But since many developers think first in SQL before translating a condition into object-oriented logic, the Doctrine_Query object may be difficult to comprehend at first. The best way to understand it is to learn from examples and sample applications. The symfony project website, for instance, is full of Doctrine_Query building examples that will enlighten you in many ways.

Every Doctrine_Query instance has a count() method, which simply counts the number of records for the query and returns an integer. As there is no object to return, the hydrating process doesn't occur in this case, and the count() method is faster than execute().

The table classes also provide findAll(), findBy*(), and findOneBy*() methods, which are shortcuts for constructing Doctrine_Query instances, executing them and returning the results.

Finally, if you just want the first object returned, replace execute() with a fetchOne() call. This may be the case when you know that a Doctrine_Query will return only one result, and the advantage is that this method returns an object rather than an array of objects.

tip

When a execute() query returns a large number of results, you might want to display only a subset of it in your response. Symfony provides a pager class called sfDoctrinePager, which automates the pagination of results.

Using Raw SQL Queries

Sometimes, you don't want to retrieve objects, but want to get only synthetic results calculated by the database. For instance, to get the latest creation date of all articles, it doesn't make sense to retrieve all the articles and to loop on the array. You will prefer to ask the database to return only the result, because it will skip the object hydrating process.

On the other hand, you don't want to call the PHP commands for database management directly, because then you would lose the benefit of database abstraction. This means that you need to bypass the ORM (Doctrine) but not the database abstraction (PDO).

Querying the database with PHP Data Objects requires that you do the following:

- Get a database connection.

- Build a query string.

- Create a statement out of it.

- Iterate on the result set that results from the statement execution.

If this looks like gibberish to you, the code in Listing 8-15 will probably be more explicit.

Listing 8-15 - Custom SQL Query with PDO

$connection = Doctrine_Manager::connection(); $query = 'SELECT MAX(created_at) AS max FROM blog_article'; $statement = $connection->execute($query); $statement->execute(); $resultset = $statement->fetch(PDO::FETCH_OBJ); $max = $resultset->max;

Just like Doctrine selections, PDO queries are tricky when you first start using them. Once again, examples from existing applications and tutorials will show you the right way.

caution

If you are tempted to bypass this process and access the database directly, you risk losing the security and abstraction provided by Doctrine. Doing it the Doctrine way is longer, but it forces you to use good practices that guarantee the performance, portability, and security of your application. This is especially true for queries that contain parameters coming from a untrusted source (such as an Internet user). Doctrine does all the necessary escaping and secures your database. Accessing the database directly puts you at risk of SQL-injection attacks.

Using Special Date Columns

Usually, when a table has a column called created_at, it is used to store a timestamp of the date when the record was created. The same applies to updated_at columns, which are to be updated each time the record itself is updated, to the value of the current time.

The good news is that Doctrine has a Timestampable behavior that will handle their updates for you. You don't need to manually set the created_at and updated_at columns; they will automatically be updated, as shown in Listing 8-16.

Listing 8-16 - created_at and updated_at Columns Are Dealt with Automatically

$comment = new Comment(); $comment->setAuthor('Steve'); $comment->save(); // Show the creation date echo $comment->getCreatedAt(); => [date of the database INSERT operation]

Database Connections

The data model is independent from the database used, but you will definitely use a database. The minimum information required by symfony to send requests to the project database is the name, the credentials, and the type of database.These connection settings can be configured by passing a data source name (DSN) to the configure:database task:

$ php symfony configure:database "mysql:host=localhost;dbname=blog" root mYsEcret

The connection settings are environment-dependent. You can define distinct settings for the prod, dev, and test environments, or any other environment in your application by using the env option:

$ php symfony configure:database --env=dev "mysql:host=localhost;dbname=blog_dev" root mYsEcret

This configuration can also be overridden per application. For instance, you can use this approach to have different security policies for a front-end and a back-end application, and define several database users with different privileges in your database to handle this:

$ php symfony configure:database --app=frontend "mysql:host=localhost;dbname=blog" root mYsEcret

For each environment, you can define many connections. The default connection name used is doctrine. The name option allows you to create another connection:

$ php symfony configure:database --name=main "mysql:host=localhost;dbname=example" root mYsEcret

You can also enter these connection settings manually in the databases.yml file located in the config/ directory. Listing 8-17 shows an example of such a file and Listing 8-18 shows the same example with the extended notation.

Listing 8-17 - Shorthand Database Connection Settings

all:

doctrine:

class: sfDoctrineDatabase

param:

dsn: mysql://login:passwd@localhost/blog

Listing 8-18 - Sample Database Connection Settings, in myproject/config/databases.yml

prod:

doctrine:

param:

dsn: mysql:dbname=blog;host=localhost

username: login

password: passwd

attributes:

quote_identifier: false

use_native_enum: false

validate: all

idxname_format: %s_idx

seqname_format: %s_seq

tblname_format: %s

To override the configuration per application, you need to edit an application-specific file, such as apps/frontend/config/databases.yml.

If you want to use a SQLite database, the dsn parameter must be set to the path of the database file. For instance, if you keep your blog database in data/blog.db, the databases.yml file will look like Listing 8-19.

Listing 8-19 - Database Connection Settings for SQLite Use a File Path As Host

all:

doctrine:

class: sfDoctrineDatabase

param:

dsn: sqlite:///%SF_DATA_DIR%/blog.db

Extending the Model

The generated model methods are great but often not sufficient. As soon as you implement your own business logic, you need to extend it, either by adding new methods or by overriding existing ones.

Adding New Methods

You can add new methods to the empty model classes generated in the lib/model/doctrine directory. Use $this to call methods of the current object, and use self:: to call static methods of the current class. Remember that the custom classes inherit methods from the Base classes located in the lib/model/doctrine/base directory.

For instance, for the Article object generated based on Listing 8-3, you can add a magic __toString() method so that echoing an object of class Article displays its title, as shown in Listing 8-20.

Listing 8-20 - Customizing the Model, in lib/model/doctrine/Article.php

class Article extends BaseArticle { public function __toString() { return $this->getTitle(); // getTitle() is inherited from BaseArticle } }

You can also extend the table classes--for instance, to add a method to retrieve all articles ordered by creation date, as shown in Listing 8-21.

Listing 8-21 - Customizing the Model, in lib/model/doctrine/ArticleTable.php

class ArticleTable extends BaseArticleTable { public function getAllOrderedByDate() { $q = $this->createQuery('a') ->orderBy('a.created_at ASC'); return $q->execute(); } }

The new methods are available in the same way as the generated ones, as shown in Listing 8-22.

Listing 8-22 - Using Custom Model Methods Is Like Using the Generated Methods

$articles = Doctrine_Core::getTable('Article')->getAllOrderedByDate(); foreach ($articles as $article) { echo $article; // Will call the magic __toString() method }

Overriding Existing Methods

If some of the generated methods in the Base classes don't fit your requirements, you can still override them in the custom classes. Just make sure that you use the same method signature (that is, the same number of arguments).

For instance, the $article->getComments() method returns a collection of Comment objects, in no particular order. If you want to have the results ordered by creation date, with the latest comment coming first, then create the getComments() method, as shown in Listing 8-23.

Listing 8-23 - Overriding Existing Model Methods, in lib/model/doctrine/Article.php

public function getComments() { $q = Doctrine_Core::getTable('Comment') ->createQuery('c') ->where('c.article_id = ?', $this->getId()) ->orderBy('c.created_at ASC'); return $q->execute(); }

Using Model Behaviors

Some model modifications are generic and can be reused. For instance, methods to make a model object sortable and an optimistic lock to prevent conflicts between concurrent object saving are generic extensions that can be added to many classes.

Symfony packages these extensions into behaviors. Behaviors are external classes that provide additional methods to model classes. The model classes already contain hooks, and symfony knows how to extend them.

To enable behaviors in your model classes, you must modify your schema and use the actAs option:

Article:

actAs: [Timestampable, Sluggable]

tableName: blog_article

columns:

id:

type: integer

primary: true

autoincrement: true

title: string(255)

content: clob

After rebuilding the model, the Article model have a slug column that is automatically set to a url friendly string based on the title.

Some behaviors that come with Doctrine are:

- Timestampable

- Sluggable

- SoftDelete

- Searchable

- I18n

- Versionable

- NestedSet

Extended Schema Syntax

A schema.yml file can be simple, as shown in Listing 8-3. But relational models are often complex. That's why the schema has an extensive syntax able to handle almost every case.

Attributes

Connections and tables can have specific attributes, as shown in Listing 8-24. They are set under an _attributes key.

Listing 8-24 - Attributes for Model Settings

Article:

attributes:

export: tables

validate: none

The export attribute controls what SQL is exported to the database when creating tables for that model. Using the tables value would only export the table structure and no foreign keys, indexes, etc.

Tables that contain localized content (that is, several versions of the content, in a related table, for internationalization) should use the I18n behavior (see Chapter 13 for details), as shown in Listing 8-25.

Listing 8-25 - I18n Behavior

Article:

actAs:

I18n:

fields: [title, content]

Column Details

The basic syntax lets you define the type with one of the type keywords. Listing 8-26 demonstrates these choices.

Listing 8-26 - Basic Column Attributes

Article:

columns:

title: string(50) # Specify the type and length

But you can define much more for a column. If you do, you will need to define column settings as an associative array, as shown in Listing 8-27.

Listing 8-27 - Complex Column Attributes

Article:

columns:

id: { type: integer, notnull: true, primary: true, autoincrement: true }

name: { type: string(50), default: foobar }

group_id: { type: integer }

The column parameters are as follows:

type: Column type. The choices areboolean,integer,double,float,decimal,string(size),date,time,timestamp,blob, andclob.notnull: Boolean. Set it totrueif you want the column to be required.length: The size or length of the field for types that support itscale: Number of decimal places for use with decimal data type (size must also be specified)default: Default value.primary: Boolean. Set it totruefor primary keys.autoincrement: Boolean. Set it totruefor columns of typeintegerthat need to take an auto-incremented value.sequence: Sequence name for databases using sequences forautoIncrementcolumns (for example, PostgreSQL and Oracle).unique: Boolean. Set it totrueif you want the column to be unique.

Relationships

You can specify foreign key relationships under the relations key in a model. The schema in Listing 8-28 will create a foreign key on the user_id column, matching the id column in the blog_user table.

Listing 8-28 - Foreign Key Alternative Syntax

Article:

actAs: [Timestampable]

tableName: blog_article

columns:

id:

type: integer

primary: true

autoincrement: true

title: string(255)

content: clob

user_id: integer

relations:

User:

onDelete: CASCADE

foreignAlias: Articles

Indexes

You can add indexes under the indexes: key in a model. If you want to define unique indexes, you must use the type: unique syntax. For columns that require a size, because they are text columns, the size of the index is specified the same way as the length of the column using parentheses. Listing 8-30 shows the alternative syntax for indexes.

Listing 8-30 - Indexes and Unique Indexes

Article:

actAs: [Timestampable]

tableName: blog_article

columns:

id:

type: integer

primary: true

autoincrement: true

title: string(255)

content: clob

user_id: integer

relations:

User:

onDelete: CASCADE

foreignAlias: Articles

indexes:

my_index:

fields:

title:

length: 10

user_id: []

my_other_index:

type: unique

fields:

created_at

I18n Tables

Symfony supports content internationalization in related tables. This means that when you have content subject to internationalization, it is stored in two separate tables: one with the invariable columns and another with the internationalized columns.

Listing 8-33 - Explicit i18n Mechanism

DbGroup:

actAs:

I18n:

fields: [name]

columns:

name: string(50)

Behaviors

Behaviors are model modifiers provided by plug-ins that add new capabilities to your Doctrine classes. Chapter 17 explains more about behaviors. You can define behaviors right in the schema, by listing them for each table, together with their parameters, under the actAs key. Listing 8-34 gives an example by extending the Article class with the Sluggable behavior.

Listing 8-34 - Behaviors Declaration

Article: actAs: [Sluggable] # ...

Don't Create the Model Twice

The trade-off of using an ORM is that you must define the data structure twice: once for the database, and once for the object model. Fortunately, symfony offers command-line tools to generate one based on the other, so you can avoid duplicate work.

Building a SQL Database Structure Based on an Existing Schema

If you start your application by writing the schema.yml file, symfony can generate a SQL query that creates the tables directly from the YAML data model. To use the query, go to your root project directory and type this:

$ php symfony doctrine:build-sql

A schema.sql file will be created in myproject/data/sql/. Note that the generated SQL code will be optimized for the database system defined in the databases.yml.

You can use the schema.sql file directly to build the tables. For instance, in MySQL, type this:

$ mysqladmin -u root -p create blog $ mysql -u root -p blog < data/sql/schema.sql

The generated SQL is also helpful to rebuild the database in another environment, or to change to another DBMS.

tip

The command line also offers a task to populate your database with data based on a text file. See Chapter 16 for more information about the doctrine:data-load task and the YAML fixture files.

Generating a YAML Data Model from an Existing Database

Symfony can use Doctrine to generate a schema.yml file from an existing database, thanks to introspection (the capability of databases to determine the structure of the tables on which they are operating). This can be particularly useful when you do reverse-engineering, or if you prefer working on the database before working on the object model.

In order to do this, you need to make sure that the project databases.yml file points to the correct database and contains all connection settings, and then call the doctrine:build-schema command:

$ php symfony doctrine:build-schema

A brand-new schema.yml file built from your database structure is generated in the config/doctrine/ directory. You can build your model based on this schema.

Summary

Symfony uses Doctrine as the ORM and PHP Data Objects as the database abstraction layer. It means that you must first describe the relational schema of your database in YAML before generating the object model classes. Then, at runtime, use the methods of the object and table classes to retrieve information about a record or a set of records. You can override them and extend the model easily by adding methods to the custom classes. The connection settings are defined in a databases.yml file, which can support more than one connection. And the command line contains special tasks to avoid duplicate structure definition.

The model layer is the most complex of the symfony framework. One reason for this complexity is that data manipulation is an intricate matter. The related security issues are crucial for a website and should not be ignored. Another reason is that symfony is more suited for middle- to large-scale applications in an enterprise context. In such applications, the automations provided by the symfony model really represent a gain of time, worth the investment in learning its internals.

So don't hesitate to spend some time testing the model objects and methods to fully understand them. The solidity and scalability of your applications will be a great reward.

This work is licensed under the GFDL license.